Bimota Spare Parts

Search thousands of listings from verified sellers and get the exact part you need — fast, free, and without the hassle of middlemen or markups.

Select a Model:

Bimota: Rimini’s Rebels of Precision

Along the breezy Adriatic coast, where the hum of scooters and the smell of saltwater blend with the sound of engines, a small workshop in Rimini once dared to challenge the world’s biggest motorcycle factories. In 1973, three men — Valerio Bianchi, Giuseppe Morri, and a young, obsessive engineer named Massimo Tamburini — founded Bimota, a name stitched together from the first two letters of their surnames. It was the birth of a legend built not on mass production, but on precision, passion, and an almost spiritual belief that motorcycles could be as beautiful as they were fast.

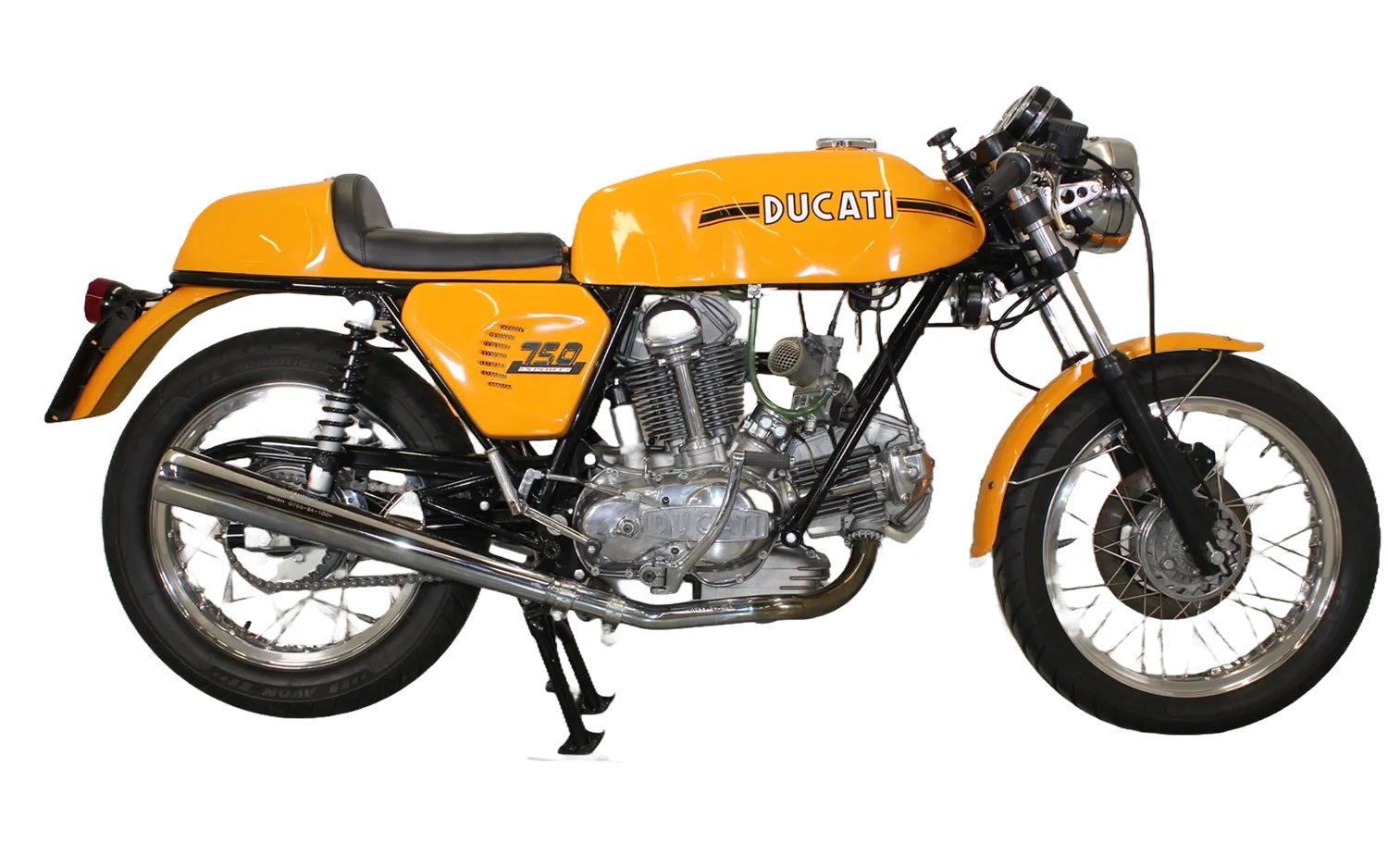

At the time, Japan’s major manufacturers were flooding Europe with powerful engines that outpaced their frames. The result was thrilling in a straight line but terrifying in a corner. Tamburini, having wrecked his Honda 750 and spent months recovering, decided the answer lay in geometry — not horsepower. Bimota’s first machine, the HB1, wasn’t an attempt to outgun Honda, but to make its power usable. Built in tiny numbers, it was a revelation. Lightweight, taut, and crafted by hand, the HB1 wasn’t just fast — it was composed, something few big bikes could claim in 1973.

Word spread through paddocks and pit lanes. Soon, other Japanese engines — Suzuki, Yamaha, Kawasaki — were arriving at Rimini’s door. Bimota’s business was never about engines; it was about what wrapped around them. Each bike wore a unique code: the first letter stood for the engine supplier, followed by the founders’ initials — hence HB for Honda-Bimota, KB for Kawasaki, YB for Yamaha. Beneath the fairings, the engineering was closer to aerospace than to mass production: hand-welded frames, magnesium components, and weight shaved away until every line served a purpose. In the late seventies, racers and privateers began ordering Bimota chassis kits to replace their stock frames, and suddenly the Rimini outfit was beating factory teams with their own engines.

Tamburini’s departure in 1983 to Ducati might have ended the story for a lesser company, but Bimota carried on with the same stubborn independence. Under Morri’s leadership, the company doubled down on experimentation. The YB4, introduced in the mid-’80s, became the first production bike in the world to use electronic fuel injection. With Virginio Ferrari at the helm, it won the 1987 Formula TT Championship — a factory-defying feat that remains one of the marque’s proudest achievements. But Bimota was already looking beyond racing. What fascinated its engineers wasn’t just speed, but control — the sensation of a motorcycle responding perfectly to its rider’s input. From that obsession came one of the most audacious ideas in motorcycle history: the Tesi project.

The Tesi (Italian for “thesis”) explored an idea few dared to attempt — hub-centre steering. Where conventional motorcycles used telescopic forks, the Tesi routed steering forces through a system of swingarms and linkages, separating braking from suspension. The result was extraordinary stability and a look that seemed to come from another planet. When the Tesi 1D finally appeared in the late 1980s, it was part motorcycle, part experiment, and entirely Bimota. No other brand would have risked so much for so little commercial gain, and that’s precisely why the Tesi became iconic.

Through the 1990s, the Rimini firm continued to turn out rolling sculptures — the Ducati-powered DB series, the Yamaha-based YB6 Exup, and the flamboyant SB6 with Suzuki’s GSX-R engine. Each was built in limited numbers, assembled almost like a watch, and priced accordingly. But perfection came at a price, and the market for handcrafted Italian exotics was never large. Then came the Vdue — a 500cc two-stroke designed and built entirely in-house, meant to prove that Bimota could stand on its own. Instead, it nearly destroyed them. The Vdue’s direct fuel injection was years ahead of its time but plagued with problems. Bimota’s reputation for flawless engineering took a hit, and in 2000 the company filed for bankruptcy. The factory lights in Rimini went out, and for a moment, it seemed the legend had run its course.

But legends have a way of returning. Within two years, a small group of investors revived Bimota, and the brand’s rebirth was every bit as defiant as its creation. The DB5 and DB6 Delirio carried the same handmade DNA — trellis frames, exposed mechanics, and an almost architectural precision. Production was still tiny, but that was part of the magic. Owning a Bimota wasn’t about owning transportation; it was about owning intent.

In the 2010s, the Tesi name returned once again — this time as the Tesi 3D, a piece of kinetic art that combined Ducati power with Bimota’s relentless experimentation. Each model that followed, from the DB7 to the DB8, was a statement that innovation didn’t need a large factory, just the courage to build differently. Then in 2019, the story took a turn few expected: Kawasaki Heavy Industries acquired a 49% stake in Bimota. The partnership gave the Rimini artisans access to cutting-edge technology and stability, but the essence remained intact. The Tesi H2, unveiled later that year, paired Kawasaki’s supercharged engine with Bimota’s radical chassis design — a mechanical handshake between discipline and madness.

Today, Bimota operates more like an atelier than a manufacturer. Each bike is built to order, by hand, in the same town where it all began. The new KB4 — a modern reinterpretation of the 1970s KB series — reminds the world that nostalgia and innovation can share the same bodywork. With production limited to just a handful of units per year, Bimota remains a motorcycle built for the few who understand that speed can also be art.

Bimota’s story isn’t one of volume, or even of constant success. It’s the story of a company that believed in engineering purity above all else — a story that begins and ends with the curve of a frame, the balance of weight and power, and the stubborn belief that there’s always a better way to build a motorcycle. From the HB1 to the Tesi H2, every Bimota has been a thesis on obsession — and Rimini’s small workshop continues to prove that obsession, in the right hands, is a kind of genius.

Other Manufacturers

Have something to sell? Sign up free

Spare parts gathering dust? Put them online in minutes. It’s free, easy, and made for sellers like you. You can get selling with just a few photos and a quick description.